Theory of Change: a tick-box exercise?

Billy Wong’s recent article is excellent, and he makes a really important point: Theory of Change was originally designed as a way to think, but in some areas is becoming a ‘compliance’ tool. It was never meant to be a form to complete at the end of a funding bid, but it’s in danger of becoming exactly that.

There is one part of this, however, where I take a slightly different view.

Wong raises concerns about the use of simplified Theory of Change models:

“The increasing popularity and wider usage of Theory of Change (ToC) should be a cause for celebration,

but the mass adoption in a simplified and abstract way has become a cause for concern.”

I agree with the concern, but I’d argue that the problem isn’t simplified templates.

I’d also argue that simplified templates have a value and an important role to play.

The problem is what happens around them.

Spending time

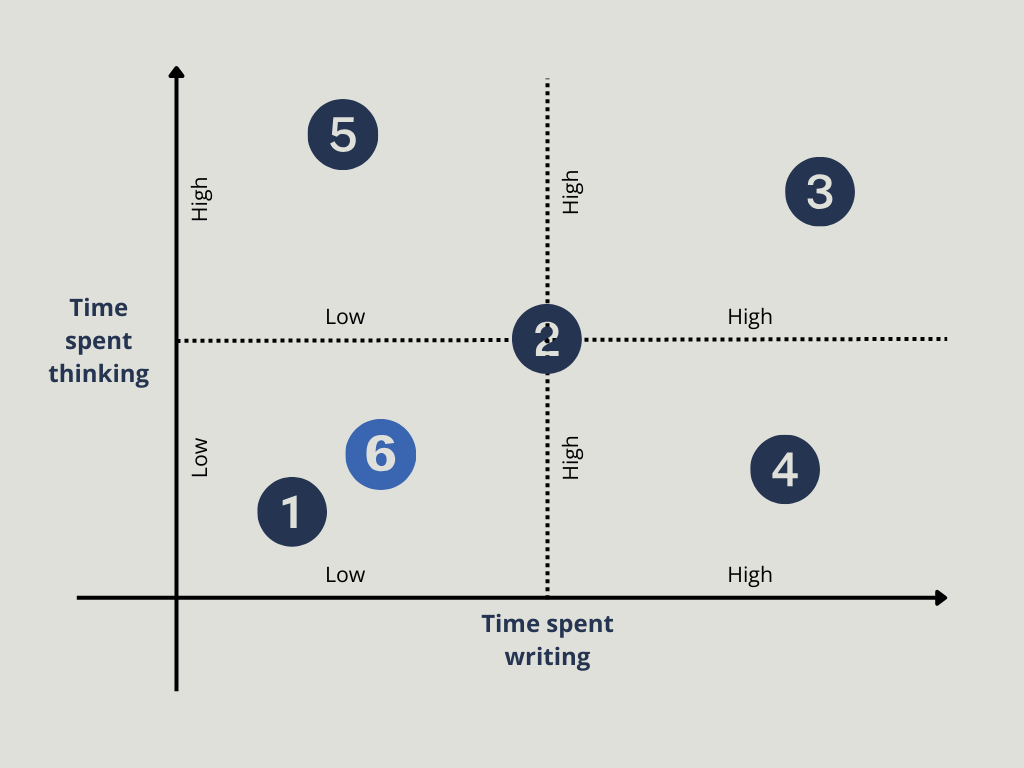

When completing a ToC, I believe there are two main things that take up the time: thinking and writing. How people divide their time can be mapped. I presented below model at NTU and with TASO recently, describing exactly what I mean.

When completing a ToC, I believe you can fall into one of these categories

New or disengaged users > people who don’t spend much time on ToC at all. These are exactly the people I want to reach.

Budding evaluators > I work with a lot of these people at NTU. People who spend time thinking and writing, and are actively engaging with the process.

The academic experts > people who produce beautiful, complex, and theoretically rich ToCs. These are valuable, but they’re not accessible to everyone.

The frustrated practitioner > many people engaging with Theory of Change can end up here. People who spend a lot of time trying to write a ToC but get tangled in unfamiliar language and concepts, and end up resenting the process.

The efficient ToC machine > people who, with the right tools and guidance, spend most of their time thinking, and very little time struggling with the writing.

The form fillers > the danger zone, where people use simplified tools to produce “quick and dirty” ToCs with very little thinking behind them.

The risk Wong points to is real. But I’d argue that people don’t end up in category 6 because templates are simple. They end up there because of a lack of time, a lack of support, and a lack of understanding about why Theory of Change matters.

Protecting time

Good templates don’t replace thinking. They make space for it.

But that only works if the conditions are right. If people are rushed, unclear about the purpose, or simply told to “complete this by Friday,” then any tool becomes a tick-box exercise. That’s not a failure of the template, it’s a failure of the environment around it.

With the right structure, guidance, and protected thinking time, we can help people move from being frustrated or disengaged into becoming thoughtful and confident users.

There is also another reason simplified Theory of Change models matter.

Theory of Change is not just a thinking tool, it’s a communication tool.

Time well spent

A simplified ToC turns internal thinking into shared understanding. It helps managers see what they are funding, partners see how they fit in, practitioners see what they are aiming for, and stakeholders see why the work matters.

It cuts down on ‘decoding’ time, making research and evaluation accessible to non-experts.

That’s why clarity matters, and why a simplified ToC is so important.

If a Theory of Change is written in technical language that only a few people understand, then it stops doing its job. It doesn’t travel. It doesn’t invite discussion. It doesn’t support learning. Academic and complex ToCs have an important place, but they are often only usable by other experts.

Simplifying Theory of Change (providing the thinking time remains) doesn’t mean making it shallow. It makes it visible.

It means:

Using everyday language instead of jargon

Focusing on the main pathways of change

Making need, assumptions, and rationale visible

Creating something people feel able to question, use, and improve.

Billy Wong is absolutely right to warn against turning thinking into tick-boxing.

But I’d argue the answer isn’t to abandon simplified templates. It’s to use them well, support them properly, and surround them with time, purpose, and conversation.

Authors note: I’d genuinely encourage you to read Billy Wong’s article. Not only is it well written and well argued, it demonstrates that he is someone to listen to in this space! Find Billy Wong on LinkedIn for more.