Evaluation and Theory of Change… why should I care?

If you work in education, your local community, at a charity or non-profit, a volunteering group, or other public sector organisation, I know what your priority is.

It’s not frameworks.

It’s not diagrams.

It’s not evaluation.

It’s people.

It’s delivering your work, supporting those who need it, responding to what’s in front of you, and doing your best with limited time and resources. The idea pausing that to work on something called a “Theory of Change” can feel, at best, like a luxury or maybe a distraction.

So why should you care?

Why is it necessary?

When working at TASO, I was told a real-life example that stuck with me.

In the US in the 1970s, a social programme was delivered to young people at-risk of falling into crime later in life. This programme was called ‘Scared Straight’ where kids were taken into prisons, to deter them from going down that path. The programme was delivered with good intentions, and everyone thought they were doing a good thing.

When researchers finally started to evaluate it over a decade later, they found that not only did it not work, but it made the kids more likely to commit crimes, not less.

The people delivering this programme did not have an evidence-based approach for what they were doing, and hadn’t thought about how to measure impact.

There was no Theory of Change, and no evidence based planning or thinking involved.

What is a Theory of Change?

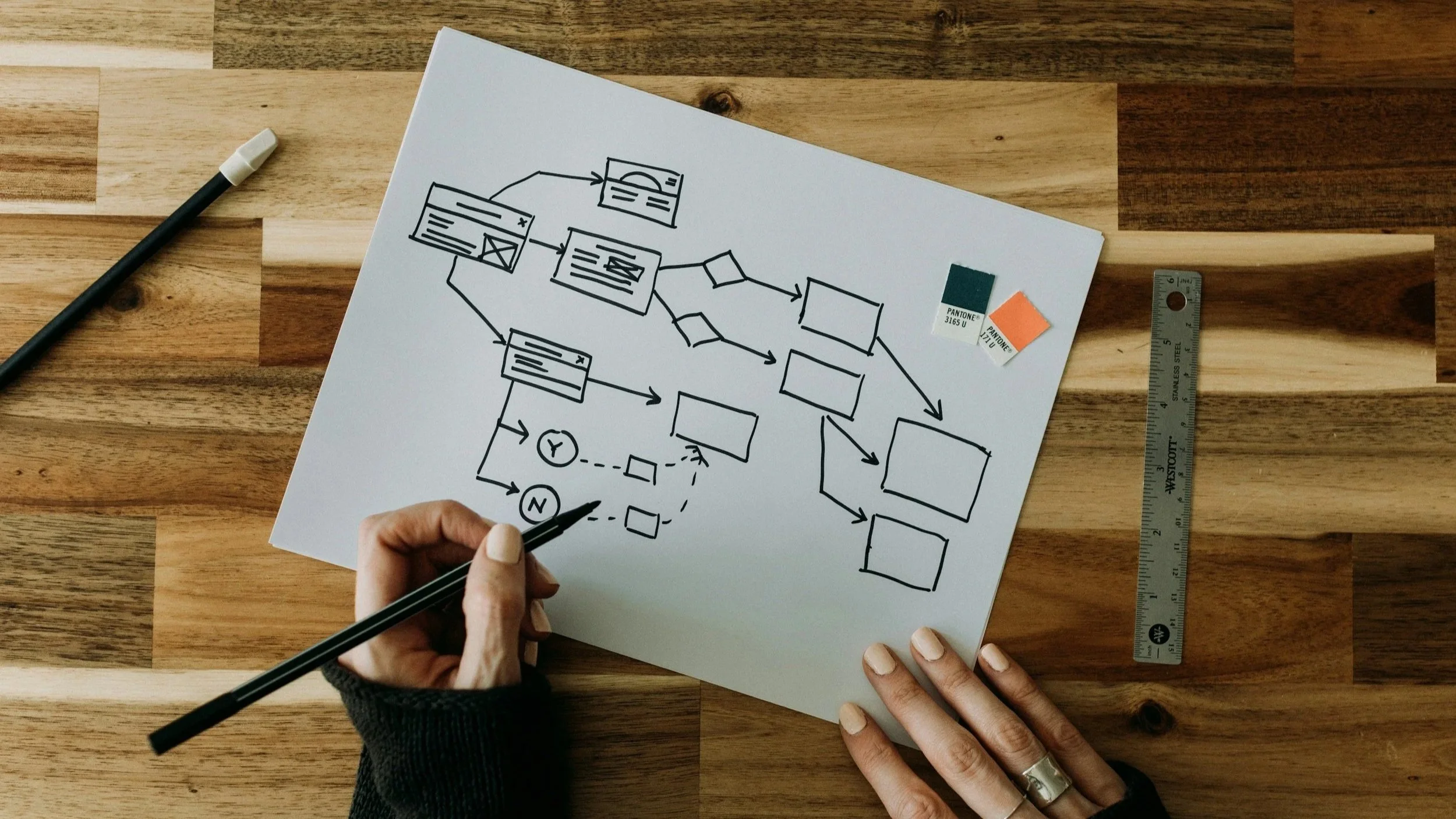

A Theory of Change is simply a way of making your thinking visible. It helps you clarify what problem you’re trying to address, who your work is really for, what change you’re hoping to see, and how you think your activities actually lead to that change.

You probably already have answers to these questions in your head. But they’re often changing with time, different depending on who you ask, or buried under day-to-day pressures.

A Theory of Change gives you a shared version of that thinking.

From my work in Widening Participation in Higher Education and working with schools, colleges, charities, and community partners, I’ve seen how powerful this can be.

What does it give you?

When teams take the time to build and develop a Theory of Change, a few things happen:

They become clearer about what they’re trying to do and why.

They spot gaps, assumptions, or risks they hadn’t noticed before.

They start asking better questions about whether their work is helping in the way they think it is.

They communicate more clearly with funders, partners, and each other.

It doesn’t slow work down. It often stops people doing things that don’t help, like what happened on those Scared Straight programmes.

And that’s why it’s worth the time.

What can you do next?

The problem is that Theory of Change is often presented in very academic or technical ways, which makes it feel inaccessible and intimidating. This is especially true if you don’t see yourself as an “evaluation person.”

That’s why I take a simplified approach.

Not simplified in the sense of shallow or basic, but simplified in the sense of clear, focused, and usable. Using plain language. Asking simple questions. Creating space for thinking rather than lots of writing.

The value isn’t in ending up with a beautiful diagram (although they can be beautiful), the value is in having shared clarity.

If you’re curious about Theory of Change, unsure whether it’s relevant for you, or worried it will be more work than it’s worth, I’d love to help.

No jargon. No judgement. Just thinking, learning, and building together.

If that sounds useful, get in touch.